Lumbar Puncture Teaching

Welcome to the Lumbar Puncture teaching platform.

This has been created to help guide clinicians who may be required to perform a lumbar puncture. It offers a concise knowledge base for reference and reassurance.

The platform has been created by experienced clinicians, but is not designed to replace clinical judgement or competency.

We would recommend taking some time to familiarise yourself with the platform which is separated into different sections.

If you have any feedback, we would be delighted to hear from you.

To see a full video demonstration of a Lumbar Puncture, please click here to go to the Video Demonstration section.

Video demonstrations

CT Head?

It is an absolute contra-indication to perform a lumbar puncture on patients who may be at risk of coning through raised intracranial pressure.

Coning can occur when removal of CSF during an LP creates a pressure gradient. With raised intracranial pressure, the gradient can be big enough to displace the cerebellar tonsils downwards, through the foramen magnum, and this effect is called coning. It can have a catastrophic effect on brainstem function, and can be life-threatening.

Despite this, we do perform lumbar punctures on patients with raised intracranial pressure due to Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. This is because it does not have the same risk of coning; the build of pressure originates from the fluid itself, as opposed to, for example, the mass effect of an intracranial space-occupying lesion.

In the vast majority of cases a CT Head is performed prior to an LP. As well as helping to guide a patient’s diagnosis and management, it helps to rule out space-occupying lesions and other causes of raised intracranial pressure which might prohibit carrying out an LP.

The information provided throughout this lumbar puncture website aims to help you perform a lumbar puncture safely. However, it is the absolute and total responsibility of the clinician to ensure it is safe to proceed with a lumbar puncture on a patient in their care. This may, or may not, require a CT head to be performed first.

Patient Consent

As with all procedures, you need to consent the patient prior to performing a lumbar puncture.

There is a video available for patients which explains the lumbar puncture procedure. It is important to show this to the patient in advance of the procedure. Watching it yourself will also help you understand what you need to cover when gaining consent.

Consent Form

It is best practice to have written rather than verbal consent. Consent forms may vary between trusts, but there are some key points you need to adhere to:

- Ensure you have the right patient, by checking the name and date of birth.

- Most consent forms have a number of carbon copies including a copy for the notes and the patient. If you are using patient stickers, make sure you put a sticker on every page.

Gaining Consent

Gaining consent involves explaining the procedure in a way that is understandable to patients, so that they can make an informed decision about whether or not to proceed.

In order to do this, you need to be able to convey the key points covered on this website including the indication and the steps involved in the procedure.

When explaining the procedure, make sure you tell the patient that you need to expose their entire back and feel around their pelvis. You may need to draw on their back and make a mark with a blunt object. This information, as well as the need to stay still for 20 minutes, is important to ensure patient cooperation.

At this time, it may also be worth advising patients about post-LP care to reduce headaches and discomfort.

Risks

A key component of gaining consent is explaining the risks. Alongside, you must explain how you will mitigate these risks.

Pain

For most people, the worst part of the procedure is the local anaesthetic injection at the beginning, Explain that this feels sharp, like a bee sting, but will quickly settle. If the local anaesthetic is infiltrated adequately, it should make the entire procedure relatively pain-free. Reassure the patient that if they do find the procedure uncomfortable, you can inject more local anaesthetic or reposition the needle. The effect of the local anaesthetic can last a couple of hours. After this, the patient may feel some discomfort.

Bleeding

As with any procedure where a needle is used, there is a risk of bleeding. In practice this is superficial, external bleeding, but technically there is the risk you could hit a large paravertebral vessel. However, as the spinal needles are so thin, even if you did hit a vessel, it is extremely unlikely to cause significant blood loss and would seal very quickly. Explain that there may be some dried blood under the dressing, or a bruise for a few days; this is similar to having a blood test. The dressing does not need to be replaced if it comes off.

Damage to underlying structures

The next risk is damage to underlying structures. Even though we pass through various structures between the skin and the CSF, there is no long term damage from this. Often patients may feel a shooting pain down their legs during the LP. This does not mean that you are damaging a nerve, but that you are close to a nerve. Ask the patient to tell you if they experience shooting pains so that you can reposition your needle.

Infection

All procedures pose a risk of infection. This is minimised by cleaning the back, wearing sterile gloves and using sterile equipment. The risk is low, around 1 in every 10000 patients who have a LP.

Headache

A common side effect from an LP is a headache due to the fluid shifts required to replace lost CSF. We have 100 to150ml of CSF and produce/drain around 20ml per hour. During a diagnostic LP we take between 5-10ml of CSF. This a small percentage of the total fluid and the body has the capacity to replenish it quite quickly. This means that for most people, headaches aren’t a dominant feature after a lumbar puncture. In therapeutic LPs for IIH or Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus, you will remove a far greater volume of fluid, leading to greater fluid shifts. These patients have a higher incidence of headache and may take a while longer to recover. Given IIH patients typically have a higher BMI, they may also suffer more with back pain because of the technical difficulty of performing an LP.

Failure of the procedure

It is always important to tell patients that the procedure may not be successful. Therefore you may have to try again, or ask for assistance from another colleague, the anaesthetists or the radiologists.

Poorly tolerated procedure

Unfortunately in the case of lumbar punctures there are some people who don’t tolerate the procedure very well at all. Often these people are more anxious to begin with so it’s important to address questions or concerns early and establish a good rapport, especially if they have googled the procedure beforehand.

Other points

Some consent forms will ask you to state the type of anaesthetic used. Usually this will be “local anaesthetic”, but occasionally some patients will want conscious sedation with diazepam. The usual dose is 2 - 5mg an hour before the procedure. In this case, you would need to tick “sedation” as well as “local anaesthetic”.

Equipment

Being organised and preparing your equipment prior to a lumbar puncture is key to a successful procedure.

The equipment shown below is the preferred equipment used by the clinicians who have designed this teaching platform.

Please follow your local Trust policies when gathering equipment for a lumbar puncture.

Where possible, you should use atraumatic needles.

- Dressing pack

- Sterile gloves

- Blunt filler needle

- 25G orange needle

- 21G green needle

- 5ml syringe

- Spinal needle (preferably atraumatic, optional longer one for obese patients)

- Manometer

- Chloroprep (or similar)

- Dressing

- Gauze

- 1% / 2% Lidocaine

- Sterile pots x 4 (preservative free)

- Glucose tube

- Optional blood taking equipment / tubes (depending on indication)

Patient positioning

Getting the patient into a good position is important for you, for them and for the success of the lumbar puncture.

Preparation

Ideally the patient should be in a gown. This allows you to see their entire back and also easily palpate their pelvis. They can keep their underwear on, but explain you will may need to see the top of their gluteal cleft.

If they are not wearing a gown, they will need to undo their trousers and roll them down.

It is up to the patient whether or not they wear shoes.

Sitting up or lying down

In general it is preferable to perform a lumbar puncture in the left or right lateral position; this is the only position in which manometry is accurate. Imagine the CSF chamber as a column of water. If it is upright, the pressure at the bottom will be higher than the top. But if the column of water is on its side, the pressure is evenly distributed throughout.

Even though you do not technically need the opening pressure for all LP indications, it is good practice to always measure the pressure just in case it is needed later.

Right or left lateral position?

The patient should lie on a flat, horizontal examination couch for an LP.

Sometimes you will not have a choice which side the patient lies on. If they have a painful shoulder or knee, they will want to lie on one side or another.

If they are happy to lie on either side, it is generally better for right handed clinicians to have the patient on their left side, and left handed clinicians to have the patient on their right side. It means you can use your non-dominant hand for feeling the bony landmarks of the spine.

The patient

The patient can have a pillow or two under their head, but it is important that their spine is as straight as possible.

Once they are on their side, ask them to bring their knees up to their chest as far as they comfortably can. This opens up the spaces between the lumbar vertebrae and gives you a bigger space to aim for. Unfortunately this can be difficult for people with joint pain, and for obese people with large abdomens.

Before you start, you must make sure that the patient is comfortable. They need to be able to hold the position for the duration of the procedure. You do not want them to move mid-procedure, so balance a technically suitable position, with a comfortable and maintainable position.

Marking Up

"Marking Up" is the term used for identifying where to insert the needle for a lumbar puncture. Getting this right is the most important step in performing a successful and safe lumbar puncture.

Safety

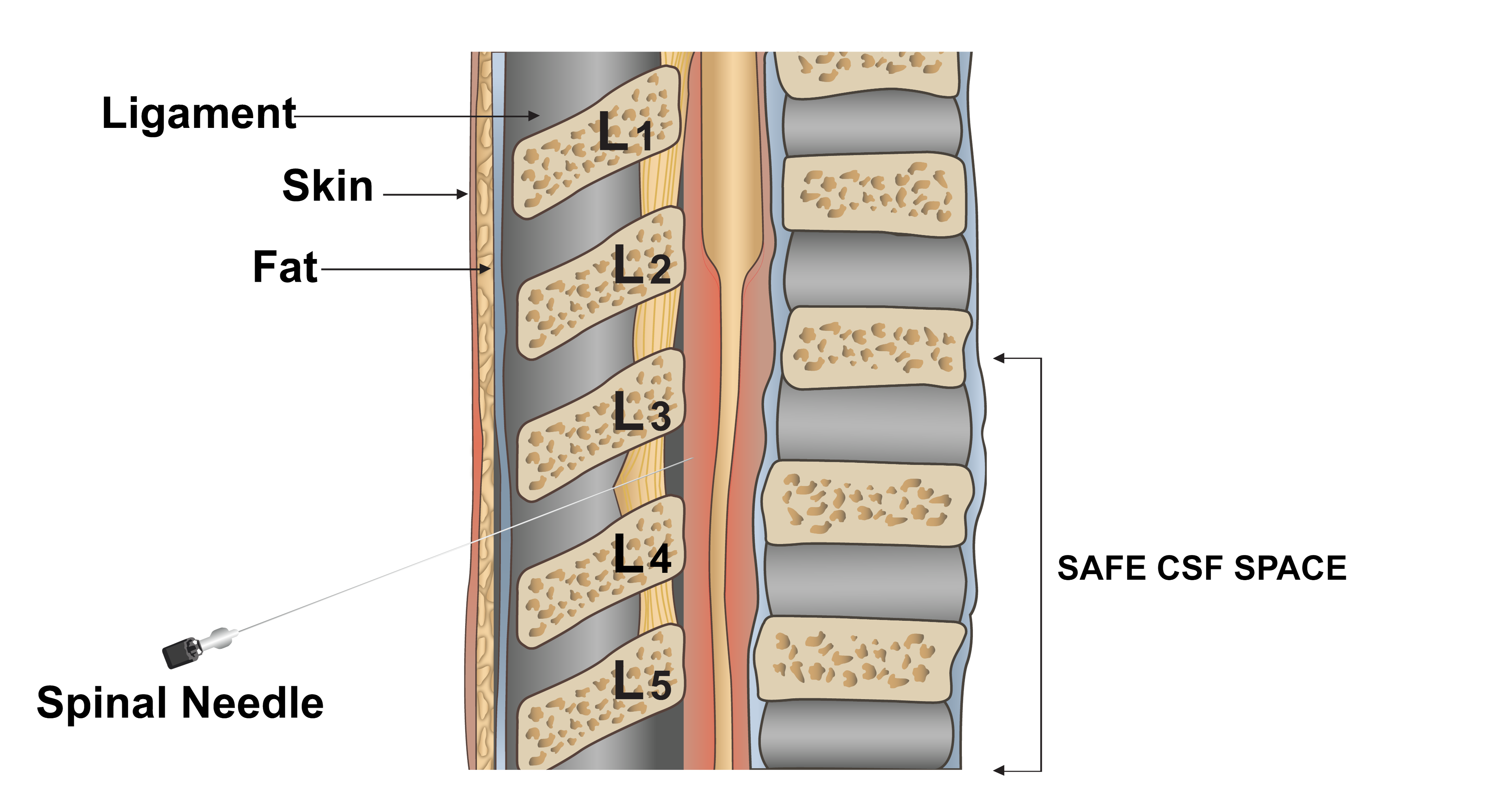

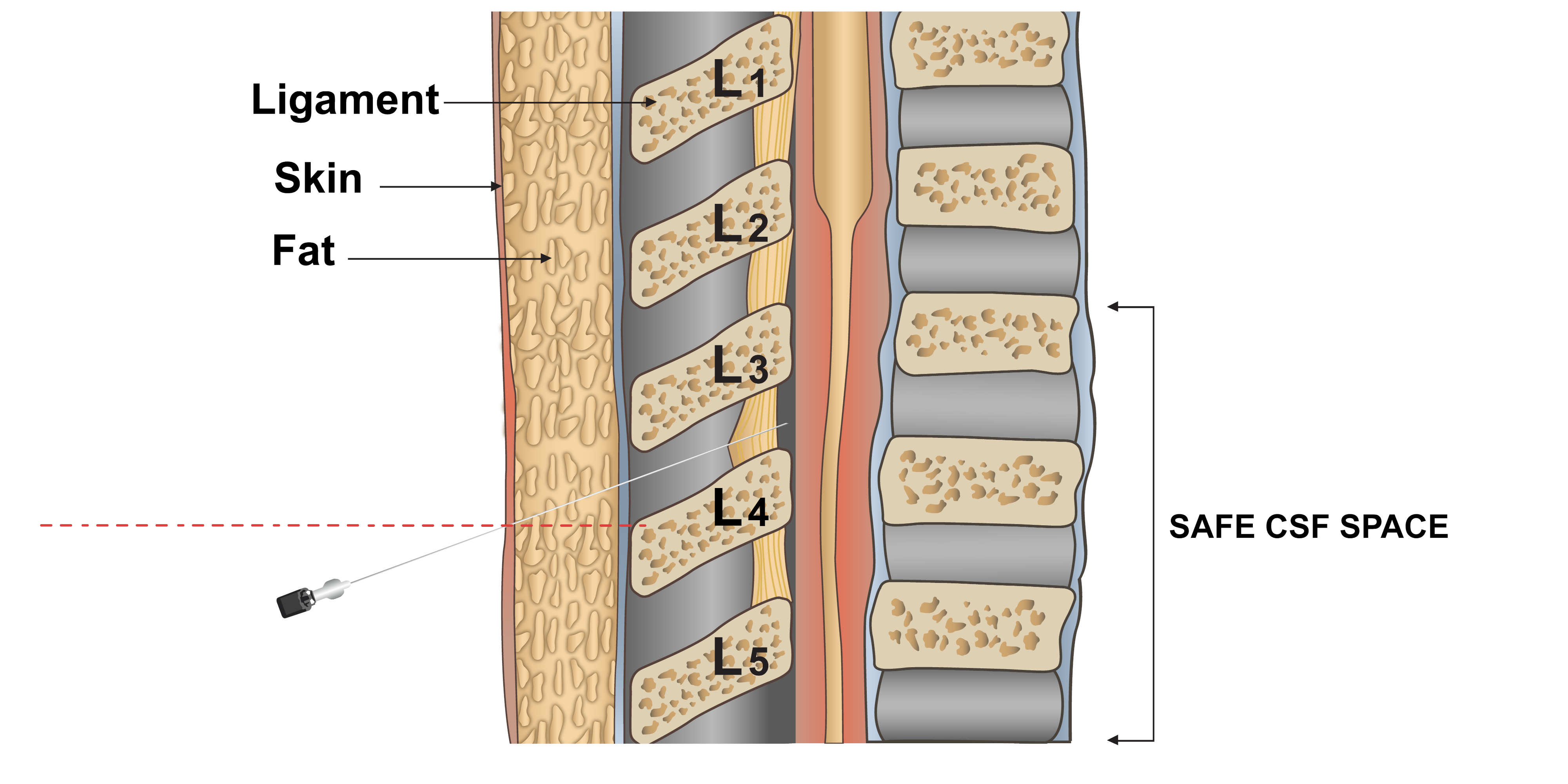

The adult spinal cord ends at the level of L1/2. Below this is the cauda equina, which translates as “horse’s tail” due to the appearance of the nerves exiting the spine. You must not perform a lumbar puncture above L2 due to the risk of damaging the spinal cord. A needle can safely be inserted below the termination of the spinal cord.

To be on the safe side, we target the space between L3 and L4 for a lumbar puncture as it is comfortably below L2. It is usually the largest and therefore the most palpable gap.

Bony Landmarks

Patient positioning is discussed in another section. For now, we assume that your patient is lying in the left or right lateral position.

The first step is to identify the level of L3/L4 using the pelvis as a landmark.

Clinicians often try and use the iliac crest as a landmark for L3/L4 but this is not accurate as it is so large, and can be difficult to feel in obese patients.

Instead, you can use the top of the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) which lines up well with L3/L4 and is more easily palpable in obese patients. You should inform the patient that you will need to feel over the front of the pelvis before you begin.

From the ASIS, you can draw a line around to the spine to find the L3/L4 level.

Finding the gap

The next step is to identify the gap between L3 and L4.

In most patients you can feel an indent between the spinous processes of L3 and L4, and this is the area for injection.

However, in very obese patients you may not be able to feel the L3/L4 gap due to the adipose tissue between the spine and skin.

In this case you need to use other landmarks to help you. Start at the neck and feel for a spinous process of one of the cervical vertebrae. Work down the spine feeling for each spinous process and marking them with a pen. When you can’t feel anymore spinous processes, use a pen to draw a line from the final, palpable spinous process to the central point of the sacrum.

Where the vertical and horizontal lines cross will be in the region of L3/L4. This gives you a starting point to palpate and to insert the needle into a safe space.

Making a mark

Once you have identified the gap between L3 and L4, you need to mark it. A pen mark will often get washed away on cleaning the skin. Therefore you can either use a blunt pen cap or a plastic bung to make an indentation in the patient’s skin. Push firmly so that the mark lasts. Warn the patient that they will feel some pushing before you do this.

Using your mark

Once again, how you use your mark varies between slim and obese patients.

In slim patients where you can feel the L3/L4 gap, you can insert the needle at your marking.

For obese patients you may need to start up to 2cm inferior to your mark.

Procedure

Prior to starting the procedure you should ensure the patient has been positioned correctly (see Positioning section) and that you have marked the L3/L4 position (see Marking up section).

Preparation

You need to have all of your equipment ready on a trolley.

Adjust the height of the bed so that the mark on the patient's back is at your chest height. This is important because you want both the anaesthetic needle and the spinal needle to be parallel to the ground. Sitting too far above or below the patient can make it difficult to judge the position of the needle and increase the chance of incorrect placement, as well as making insertion more awkward.

If you are by yourself, you will need to open the local anaesthetic now, before your hands become sterile. If someone is helping you, they can hold the local anaesthetic for you at the appropriate time.

Cleanliness

Wash your hands and put on your sterile gloves.

It helps to place a sterile sheet under the patient so that you have somewhere to rest your hands. Warn the patient that you are going to do this and tell them not to move or lift themselves up to help you out. This can change the position of your mark. Ensure your hands are tucked into the sheet to make sure your gloves remain sterile.

Now it's time to clean the patient using chloraprep. Start over the mark and make expanding circles outwards to make a large clean area. In obese patients you may want to clean right up to the neck in case you want to feel for the thoracic vertebrae. If it isn't clean, you must not touch it with sterile gloves.

You may also chose to lay a sterile sheet over the upper side of the patient so that you can feel their hip.

Local Anaesthetic

Whilst the chloraprep is drying, draw up 5ml of 1% or 2% lidocaine using a blunt filter needle. Remove the drawing up needle and replace with an orange 25G needle.

Feel again at the mark and try to feel the gap you are aiming for.

With very elderly patients who have less elastic skin, or with obese patients, the skin can sag down. You may find your initial mark is a little lower than the gap you are targeting, meaning you have to go in slightly above it.

Once you are happy with your mark, you now need to inject the local anaesthetic.

Using the orange needle, make a subcutaneous injection at the site of your mark with the needle almost flush to the skin. This means that you go into the subcutaneous tissue at a very shallow angle. This separates the layers of the skin in a transverse plane and is often less painful. It is important to have your hands anchored on the patient so that if the patient moves, you can go with them. The natural reaction to the injection is for the patient to arch their back. Without proper anchoring the needle will come out and you will have to start again.

Keeping the needle in the skin, you now need to make a path down towards the CSF space. The orientation of the needle is very important.

At all times your needle should be parallel to the floor, i.e. not pointing up and not pointing down. This often happens if you are sat too low or too high relative to the patient.

You should direct the needle towards the umbilicus. This is because the natural angle of the spinous processes means the angle of entry is somewhere between perpendicular to the back and a 45 degree angle towards the head. It is not always easy to predict what the angle will be as people have varying degrees of flexion in their lumbar spine. The diagram below demonstrates a reasonable starting point.

With the orange needle now positioned correctly, advance a few millimetres. Keeping your fingers anchored on the patient, retract the syringe plunger to ensure you are not in a vessel. If blood is withdrawn into the syringe, reposition the needle. There is no need to renew the local anaesthetic.

Inject around 0.5ml of local anaesthetic; any more than that can be painful due to the tamponade effect of the liquid. After 10 seconds, advance to the hilt of the orange needle. Once again make sure you are not in a vessel and inject a further 0.5ml lidocaine.

In some thin patients you might find that your needle is already in the supraspinous or interspinal ligament. You will know this is the case because you may feel resistance when trying to advance the needle, or that it is more difficult to inject as the ligament is tough and there is no space for the lidocaine. If this is the case, you do not need to advance any further.

Regardless of whether you have reached the ligament, withdraw the needle whilst slowly injecting a further 0.5ml lidocaine into the path you have made.

If you have reached the ligament, you do not need to inject any more local anaesthetic. You can move onto spinal needle insertion.

If you have not reached the ligament, discard the 25G orange needle and fit a 21G green needle; you need to inject more local anaesthetic down to the ligament.

There is no need repeat the subcutaneous injection with the green needle. You can insert the green needle through your original hole, in the same orientation, until half of the needle is in the patient. Now start injecting local anaesthetic in exactly the same way as you did before. Advance the green needle a small amount each time until you either hit the hilt of the needle, or you find you are in the supraspinous or interspinous ligament.

Again as you withdraw the needle, squeeze some lidocaine into your path

Inserting the spinal needle

Areas the needle can go in

Slim Patient

The dotted line demonstrates how in obese patients the point of entry needs to be lower than the L3/L4 space due to the required trajectory of the needle.

Obese Patient

Now that the area is anaesthetised, you can insert the spinal needle.

Most spinal needles have a small clip. Make sure that this is in place before using the spinal needle.

Before inserting the needle, confirm that you know where you want the needle to go. Feel for the gap and palpate the spine to make absolutely sure you are in the right place.

Once you are happy, advance the spinal needle through the same hole and along the same path as the green needle. After the needle is inserted around 3cm, have a look at your positioning from the side. Ensure that the needle is not pointing towards the floor or ceiling; it must be parallel to the floor.

Continue to slowly advance the needle. You will eventually feel a toughness. This means the needle is passing through the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments. Based on the habitus of the patient, the depth from the skin will vary.

Once you have felt this toughness, advance the needle a few millimetres. Remove the stylet fully and check for CSF in the chamber. It is essential that the stylet is fully removed, as if even part of it remains within the chamber of the needle, the CSF will be obstructed and will not flow.

If there is no CSF, you still have further to go. Replace the stylet ensuring the clip is docked.

Keep advancing the spinal needle a few millimetres at a time. After every advancement, remove the stylet and check the chamber until you see CSF.

Text books will describe a “pop” feeling or a “give” when the needle is in the right place. This occurs when the needle tents the ligament flavum, which is tougher, and then finally pierces it and enters the CSF space. If this does happen it can make the patient jump, so be prepared.

However quite often the needle pierces the ligamentum flavum and enters the CSF space with no palpable pop or give, which is why it is important to keep stopping, removing the stylet and checking the chamber for CSF.

Once you see CSF in the chamber, you are in the correct place. Put the stylet back into the needle to stem the flow of CSF. You can now move on to manometry and sample collection.

Cant find the CSF?

It is not uncommon to have difficulty finding the CSF during a lumbar puncture.

Hitting bone

The most typical problem is hitting bone. If you do hit bone, leave the needle where it is and have a look at your angle of approach both from the top, and from the side. It is likely you are hitting either the inferior edge of L3’s spinous process, or the superior border of L4.

Have a feel again for the bony landmarks. Make sure that you are at the L3/L4 space, remembering to take into account any allowances for the patient’s body habitus (see procedure section).

When you are ready to re-adjust the needle, it is good practice to withdraw the needle until it is just within the skin, and then proceed again. In this way, you stay in the same hole which may reduce the rate of infection.

Movement

A common reason for failure is the patient slipping out of position by relaxing their legs. It’s often necessary to encourage the patient to really bend their knees up as far as they can. Occasionally you may need the help of a colleague or family member to help hold their legs in place.

Lumbar punctures are not always straight forward, and you should only persevere for as long as the patient is relatively comfortable.

Post Procedure Management

Following a lumbar puncture, it is important to give advice about recovery.

Historically, patients would have been advised to lie on their back for up to a day. Now that we use smaller needles, this is not necessary. However patients should be advised to lie on their back for at least a few minutes after an LP, to put pressure over the site.

After a few minutes, sit the patient up slowly. For most patients you will only have removed a relatively small amount of CSF and they should feel fine. But in patients with IIH for example, there is a significant drop in pressure and patients can feel a little dizzy sitting up.

It is often a good idea for patients to have caffeinated drinks immediately after a lumbar puncture. Although there is no good evidence that it reduces the incidence of post-LP headache, the caffeine may help reduce any feelings of light-headedness. Many patients will often have already read about caffeine when researching lumbar punctures online.

Remember to warn patients that the local anaesthetic will continue to work for a few hours. But as it wears off, their back may become a bit more uncomfortable. You can recommend simple analgesia in the form of paracetamol and/or ibuprofen if there are no contraindications.

Patients who take anti-coagulation can restart this the following day.

Heavy lifting should be avoided for 48 hours but light exercise should be encouraged.

You can advise patients that when their dressing comes off, it does not need to be replaced. There may be a small bruise at the site which will resolve over a few days.

Procedure Write Up Notes

As with any procedure it is important to write it up clearly in the patient’s notes. With lumbar punctures it is a good idea to describe the stages you went through.

Below is an example you can use as a template. In this case it is an LP for a patient with IIH.

This is intended as a guide only and you should adapt it as necessary. For example, if you used 2% lidocaine, write this instead of 1%. In most patients you will not need to document the closing pressure (see conditions).

Example

Dr Kyle Stewart Tuesday 6th October 2020 09.00

Outpatient lumbar puncture in Outpatients Department

Written consent (see consent form within notes)

HCA Rosie Daniels as chaperone / assistant

Patient in left lateral position with knees raised

L3/L4 landmark identified and marked.

Patient cleaned with Chloraprep and allowed to dry

Aseptic technique

1% lidocaine infiltrated at L3/L4 site with 25G orange needle

Further infiltration at L3/L4 site with 21G green needle

3ml Lidocaine used

Insertion of 18G BD Quincke Spinal needle at L3/L4 site

Colourless CSF seen

Opening pressure 26cmH20

Samples taken

Additional CSF removed to achieve closing pressure 14cm H20

Spinal needle removed and dressing applied

Patient turned onto back

Mild headache for several minutes which resolved, patient felt well afterwards

Left the department with mother, advised regarding analgesia and avoiding heavy lifting for the next 24-48 hours

If headache persists to contact own GP

Neurologists will kindly chase results

Conditions

Lumbar punctures are used in the diagnosis of a number of acute, subacute and chronic medical conditions.

For each condition, you will find a link to the NHS website which provides an overview of the condition in language which is suitable for patients.

This is followed by a description and rationale for the lumbar puncture (LP) procedure and investigations that you need to perform.

It is your responsibility as a clinician to ensure that an LP is appropriate.

Acute - Subarachnoid haemorrhage

Click here to be redirected to the NHS websiteA lumbar puncture is required in the diagnosis of a subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) if the CT head is negative, but your suspicion for a SAH remains high.

The key investigation with lumbar punctures for SAH is xanthochromia. “Xantho” is Greek for yellow and “chromia” is Greek for colour. Xanthochromia therefore refers to “yellow colour”.

If someone has a SAH, blood leaks into the CSF. An enzyme reaction takes place in the CSF which turns the heme component of blood into bilirubin, turning the CSF yellow. It's the same reason your urine is yellow. It generally takes 12 hours for the enzyme reaction to occur and for xanthochromia to be present. This is why an LP should be performed 8 to 12 hours after the onset of symptoms.

Detection of xanthochromia indicates older blood in the CSF, consistent with a SAH.

Absence of xanthochromia after 12 hours means no blood is present, and therefore there is no evidence of a SAH.

Some people think that if there is an equal number of RBCs in all of the CSF samples, then this is indicative of a SAH. (Remember with all LPs, the first sample is likely to have RBCs due to the trauma caused by an LP). However, this is not a reliable diagnostic method as the same could be seen in a very traumatic LP. Xanthochromia measurement is best practice.

Key things to remember:

When you are performing an LP for a suspected SAH, there are a number of things you must remember:

- Before you start, inform the biochemistry lab that you have a sample coming as they need to prepare for its arrival

- Sample pots 1 and 3 need to be sent to haematology for the cell count. As described above, we would expect there to be more RBCs in sample 1 due to the trauma of the LP

- Either sample 2 or 4 needs to be sent to biochemistry for Xanthochromia. This sample must be protected from light as xanthochromia degrades in light. The collection bottle must be wrapped in foil or covered by an envelope during collection, as well as when it is sent to the lab.

- Take any other samples that you require

- Deliver the samples to the lab by hand. The bilirubin can disappear over time which is why you need to get the sample there as quickly as possible. Do not rely on a pod system, nor should you wait for a porter.

- It is good practice to take a blood sample for LFTs simultaneously to demonstrate that any bilirubin in the CSF is due to a bleed, rather than raised serum bilirubin

Acute - Meningitis / Encephalitis

Click here to be redirected to the NHS website Click here to be redirected to the NHS websiteA patient will require a lumbar puncture if you suspect that they have meningitis and/or encephalitis, in order to identify a virus or other causative organism.

As part of the LP, you should document the opening pressure; you may find that it is raised. This is due to the swelling of the brain and other structures, and is secondary to the condition. The fluid may be appear more turgid and less transparent due to the abundance of pus cells in bacterial meningitis.

You need to request the following CSF investigations:

- MC&S

- Cytology - It is important to request cytology rather than cell count as this gives you the differential (lymphocytes, neutrophils etc) rather than just the number of red and white cells. This helps you to determine the aetiology.

- Protein

- Glucose

- Viral PCR

You must also check the blood glucose level simultaneously.

This table will help you to interpret the results of the LP:

| Normal | Bacterial meningitis | Viral meningitis | Fungal meningitis | TB Meningitis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Clear and colourless | Cloudy and turbid | Clear | Clear or cloudy | Opaque (fibrin web if allowed to settle) |

| Opening pressure (cm H2O) | 9-17 | ^ | Normal / ^ | ^ | ^ |

| WCC (cells/uL) | 0-5 | ^ (primarily polymorphonuclear leukocytes) | ^ (primarily lymphocytes) | ^ | ^ |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 2.8-4.2 (or >60% plasma glucose conc) | Down | Normal | Low | Low |

| Protein (g/L) | 0.15-0.45 | ^ | ^ | ^ | ^ |

Reference

Sub-acute - Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

Click here to be redirected to the NHS websiteIdiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) can cause positional headaches and blurred vision. Patients will typically be overweight, younger females in their 20s and 30s. IIH used to be called Benign Intracranial Hypertension but it is not a benign condition as it threatens someone’s sight, therefore this name has been abandoned.

A lumbar puncture is required in both the diagnosis and initial treatment of IIH.

Due to the typical body habitus of patients with IIH, an LP may be technically difficult. You may find you need a longer spinal needle to reach the spine. This should only be attempted if you are confident undertaking the procedure.

In contrast to other conditions where analysis of CSF is the focus, in these patients it is the opening pressure which is important.

Diagnosis

Normal CSF pressures tend to range from 9-17cmH20.

In IIH, the CSF pressure is typically above 25cmH20 and in some patients will be over 40cmH2O. This may be above the capacity of a standard manometer. Some manometers allow you to add sections of tubing to gain an accurate measurement. But don't worry if you can’t do this. Just record the opening pressure as >40cmH2O as this level is already diagnostic.

Along with measuring the opening pressure, it is seen as good practice to send a routine sample of CSF because you have access to it. This usually encompasses:

- MC&S

- Cell Count

- Protein

- Glucose

Treatment

The aim of treatment is to reduce intracranial pressure. Once you have taken CSF samples, allow about 10ml of CSF to drain away. Aim for a final pressure of 14-18cmH2O.

You can use the same manometer to measure closing pressure. You may end up measuring the pressure several times during the procedure, and removing a little more each time before you get to the right pressure.

As you repeatedly recheck the pressure during this procedure, you may find that the manometer contains bubbles. You need to subtract these to get an accurate value.

In some patients this procedure will lead to a huge pressure drop and they may feel sick or dizzy. If this is the case, you should stop.

Chronic - Demyelinatiom

Click here to be redirected to the NHS websiteIf you suspect that a patient has multiple sclerosis (MS), a lumbar puncture is a useful diagnostic tool. It is likely that the patient will already have had imaging that demonstrates areas of demyelination in the brain and spinal cord. They may also have had an EMG and nerve conduction studies.

The key investigation is analysis of CSF for oligoclonal bands.

Oligoclonal bands are extra bands that represent immunoglobulins when CSF is analysed via PCR (polymerase chain reaction).

Immunoglobulins within the CSF are suggestive of a demyelinating processes such as MS, but can also occur in viral encephalitis, bacterial meningitis, neurosyphilis, sarcoid and lupus.

To help differentiate the causes of oligoclonal bands, you need to send a blood sample as well. This is because serum IgG can pass into the CSF. This occurs in a number of infective and inflammatory processes including HIV and autoimmune conditions.

Presence of oligoclonal bands in the CSF alone is suggestive of intrathecal synthesis and therefore a CNS condition.

You need to send:

- CSF and serum samples for oligoclonal bands, protein and glucose

- CSF samples for MC&S and cell count

Subacute - Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) presents with a triad of gait disturbance, short term memory loss and urinary incontinence. A CT head will classically show large, dilated ventricles. A lumbar puncture can be therapeutic for these patients. Removing CSF helps to restore normal brain architecture which will hopefully lead to an increase in function. The response can be dramatic.

The process of performing a lumbar puncture for NPH is longer than with other LP indications because you need to assess cognition and gait before and after the procedure.

You can assess cognition using a MOCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) or an ACE-III (Addenbrooks Cognitive Assessment).

You can assess gait using a timed 10m or 20m walk, or the “Get up and go" test which only needs 3m of space and is a validated tool.

Once you have this baseline data, you can perform the lumbar puncture. Typically the aim is to remove 40ml of CSF, but recommendations vary. This takes a long time, so make sure you and the patient are comfortable. Remember, you will find a normal opening pressure, as the name suggests. As you have access to the CSF, it is sensible to send samples for routine analysis.

You should repeat the cognitive and gait assessments an hour after the LP, although in some people this may be too early to see any real improvements. Often improvement is seen over the following days and weeks.